-

Triplet photosensitizers (PSs) have become a research hotspot in recent years due to their wide applications in fields such as photodynamic therapy [1−3], photovoltaic cells [4], and triplet-triplet annihilation upconversion [5−8]. High-efficiency triplet-state photosensitizers possess outstanding photo-stability, superior light-capturing capabilities in the visible spectrum, enhanced intersystem crossing (ISC) efficiency, and high triplet quantum yield, coupled with a long lifetime of the triplet excited state [9−11]. Nevertheless, achieving all these desirable properties in a single PS remains a significant challenge.

Traditional triplet PSs are usually based on single chromophore, resulting in a narrow absorption band within the visible spectrum [12, 13]. This limitation restricts their light-capturing capability, significantly constraining their application in many areas. Despite efforts to enhance the light-capturing capabilities of PSs for visible light by synthesizing PSs containing two or more chromophores, such as dyads or triads, in recent years, the variety of these PSs remains limited [14−16]. Moreover, the mechanism by which interactions between different chromophores affect the quantum yield of the PS’s triplet state and other properties requires further in-depth investigation.

BODIPY has gained widespread attention in recent years due to its excellent photothermal stability, good biocompatibility, high molar extinction coefficient in the visible light region, and ease of functionalization [17−19]. However, BODIPY itself only produces a very narrow absorption around 500 nm and cannot undergo ISC to generate triplet excited states. By incorporating heavy atoms such as iodine into the β-position of BODIPY, we can achieve a dual benefit: not only doing it results in a redshift of BODIPY’s absorption spectrum towards longer wavelengths (at about 540 nm), but it also facilitates ISC via the heavy atom effect, thereby enabling the generation of triplet excited states [20].

3,4,9,10-Perylenetetracarboxylic dianhydride (PDA) shows a good light capture ability with excellent photochemical and thermal stability [21−23]. Moreover, this type of chromophore has strong light-harvesting capabilities around 550–620 nm, which can complement the light-harvesting range of iodinated BODIPY. Moreover, since the first excited state energy level of PDA is lower than that of BODIPY, it can function as an effective energy acceptor for BODIPY.

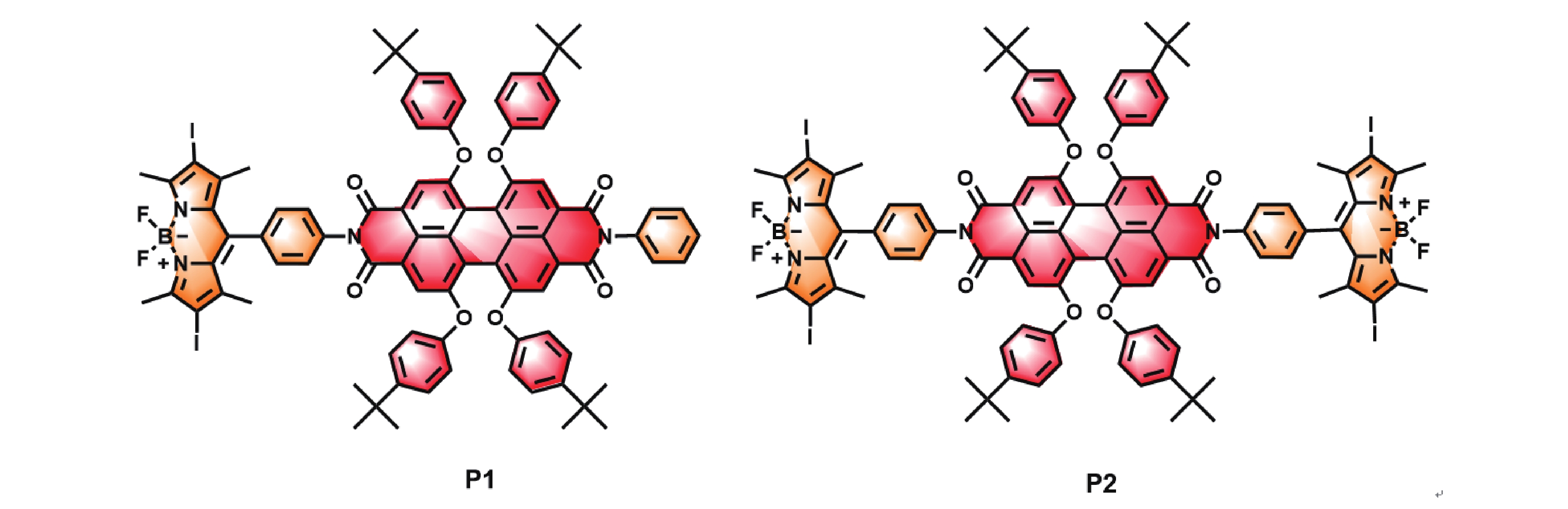

Hence, we designed and synthesized a dyad, P1, containing one diiodo-BODIPY and one PDA, and a triad, P2, containing two diiodo-BODIPYs and one PDA. The molecular structures of the two compounds are given in FIG. 1. The photophysical processes and photooxidation capacities of these two compounds were also studied. Both P1 and P2 exhibit high molar extinction coefficients in the 400–620 nm range. Upon excitation of diiodo-BODIPY, it can transfer the energy from its singlet excited state to PDA. Due to the presence of heavy atoms, PDA can then undergo intersystem crossing to produce a triplet excited state. With two diiodo-BODIPY units, P2 generates the triplet excited state more efficiently and also demonstrates superior photooxidation capabilities.

-

The synthesis routes of compounds P1 and P2 are shown in Scheme 1, and the synthetic details are provided in the Experimental Section of the Supplementary materials (SM). According to previously reported methods [14], nitro boron-dipyrromethene B1 was synthesized from 2,4-dimethylpyrrole and p-nitrobenzaldehyde via a one-pot method. Then, under acidic conditions, using NIS (N-iodosuccinimide) as the iodinating agent, the diiodo-BODIPY B2 was synthesized. Subsequently, B2 was reduced by hydrazine hydrate to obtain compound B3. Finally, B3 reacted with PDA under the catalysis of imidazole to carry out the amide reaction, synthesizing a monomeric intermediate containing one diiodo-BODIPY group and P2 with diiodo-BODIPY moieties on both sides. Due to the strong adsorption of PDA’s monoanhydride containing one diiodo-BODIPY on column chromatography, making it difficult to separate, this reaction step proceeded without separation and was directly followed by reaction with aniline. After separation and purification, 31% of P1 and 52% of P2 were obtained.

The synthesized compounds exhibit good solubility in common solvents, which facilitates the structural characterization of each compound. The structures of the intermediates and the target products P1 and P2 were characterized using nuclear magnetic resonance spectrum (NMR) and high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS), with the results shown in FIGs. S1–S9 in Supplementary materials (SM).

FIG. 2 displays the expanded 1H NMR spectra of P1 and P2. From FIG. 2(a), it can be observed that two peaks at chemical shifts of 8.30 and 8.24 ppm correspond to the signals of the four hydrogen atoms on the PDA skeleton; the signals at chemical shifts ranging from 7.52 ppm to 6.84 ppm are attributed to the hydrogen atoms on the benzene rings; the 36 hydrogens at chemical shifts of 1.28 and 1.26 ppm are the signals of the tertiary butyl groups, and the hydrogens at chemical shifts of 2.64 and 1.51 ppm are those on the pyrrole rings. These all match the structure of P1. Similarly, the 1H NMR spectrum in FIG. 2(b) is completely consistent with the structure of P2.

In the 13C NMR (FIGs. S5 and S8 in SM) of P1 and P2, there are 18 and 15 lines appearing in the chemical shift range of 119–164 ppm respectively, corresponding to the aromatic carbons, which align with the molecular symmetry. Finally, HRMS was also used to characterize the structures of P1 and P2. The relative molecular masses of P1 and P2 were determined to be 1633.3968 and 2130.2978, respectively, which are consistent with the calculated molecular weights. Therefore, combining all the analyses above, the structures of P1 and P2 can be confirmed.

-

The UV-Vis absorption spectra of P1, P2, and the reference compounds B3 and PDA are recorded in toluene and presented in FIG. 3(a). B3 (4-(5,5-difluoro-2,8-diiodo-1,3,7,9-tetramethyl-5H-4l4,5l4-dipyrrolo[1,2-c:2',1'-f][1,3,2]diazaborinin-10-yl)aniline) exhibits a particularly strong absorption peak at 537 nm, while PDA shows a weak absorption peak at 528 nm and a strong absorption peak at 577 nm. Both P1 and P2 have a strong absorption peak at 537 nm and a slightly weaker absorption peak at 577 nm, corresponding to the absorptions of B3 and PDA, respectively. Moreover, as P2 contains two iodine-substituted BODIPYs, its absorption at 537 nm is nearly twice that of P1. The UV-Vis spectrum indicates that linking BODIPY and PDA together effectively achieves a complementary absorption in the visible light region, endowing P1 and P2 with strong light-harvesting capabilities across the 400–620 nm range. Compared to the monomeric units, there is no significant red or blue shift in the absorption peaks of P1 and P2, only an overlay of absorption intensity and range. This suggests that in their ground state, the energy donor (BODIPY) and energy acceptor (PDA) are independent of each other, with no strong electronic interaction between them [24].

To investigate the properties of P1 and P2 in their excited states, their luminescence characteristics were studied using excitation light of different wavelengths. The results are shown in FIG. 3(b–d). Exciting P1 and P2 at 489 and 532 nm, would preferentially excite the diiodo-BODIPY part. As shown in FIG. 3(b, c), B3 exhibits an emission peak at 556 nm, while PDA shows a strong emission peak at 603 nm. Theoretically, if there is no energy or electron transfer, when selectively exciting the diiodo-BODIPY part, the fluorescence intensity of P1 at 556 nm should be the same as that of B3; the fluorescence intensity of P2 at 556 nm should be twice that of B3. However, in P1 and P2, the corresponding emission peaks were not observed, indicating that the introduction of PDA causes the fluorescence of BODIPY to be quenched [16]. In addition, compared to PDA without diiodo-BODIPY, the emission peaks at 603 nm belonging to the PDA part in P1 and P2 are enhanced, and the fluorescence intensity of P2, which contains two B3 units, is stronger. This observation further demonstrates that in P1 and P2, upon excitation of the diiodo-BODIPY moiety, there is an effective transfer of singlet excited energy to the PDA component with the energy transfer efficiency nearing 100%. This process leads to the quenching of fluorescence of the diiodo-BODIPY moiety and the enhancement of the emission from PDA.

When excited at 580 nm, only the PDA unit is selectively excited. Considering that the absorption cross-sections of PDA, P1, and P2 at 580 nm are similar, the generated PDA singlet excited states should also be similar. However, according to the fluorescence spectra shown in FIG. 3(d), the fluorescence intensity of PDA is higher than that of P1, and the fluorescence intensity of P1 is higher than that of P2. This indicates that the fluorescence of the PDA part in P1 and P2 has been quenched. It is speculated that the introduction of the diiodo-BODIPY enhances the ISC of PDA, and because P2 introduces two diiodo-BODIPY units, the ISC rate of P2 is accelerated.

-

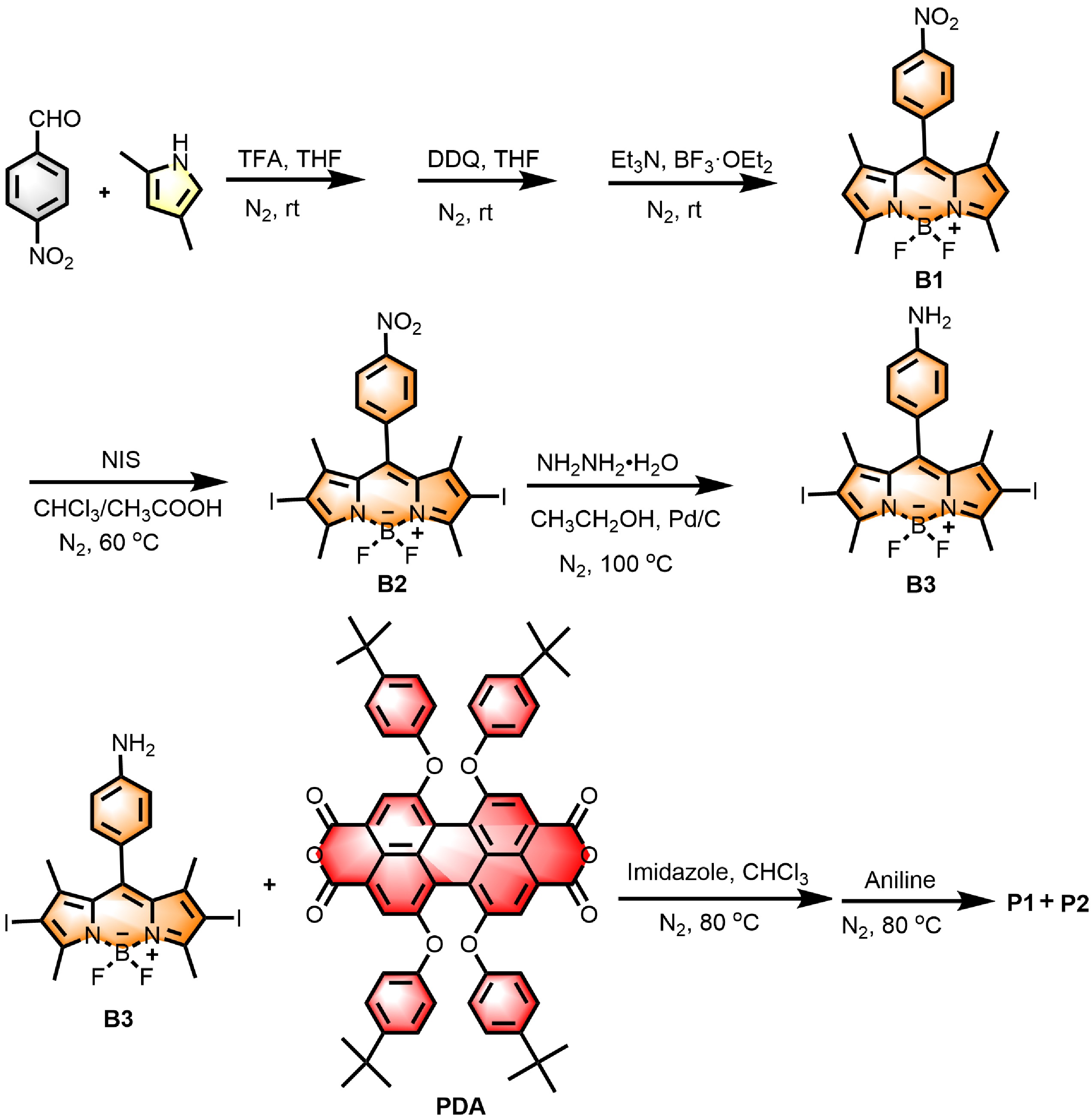

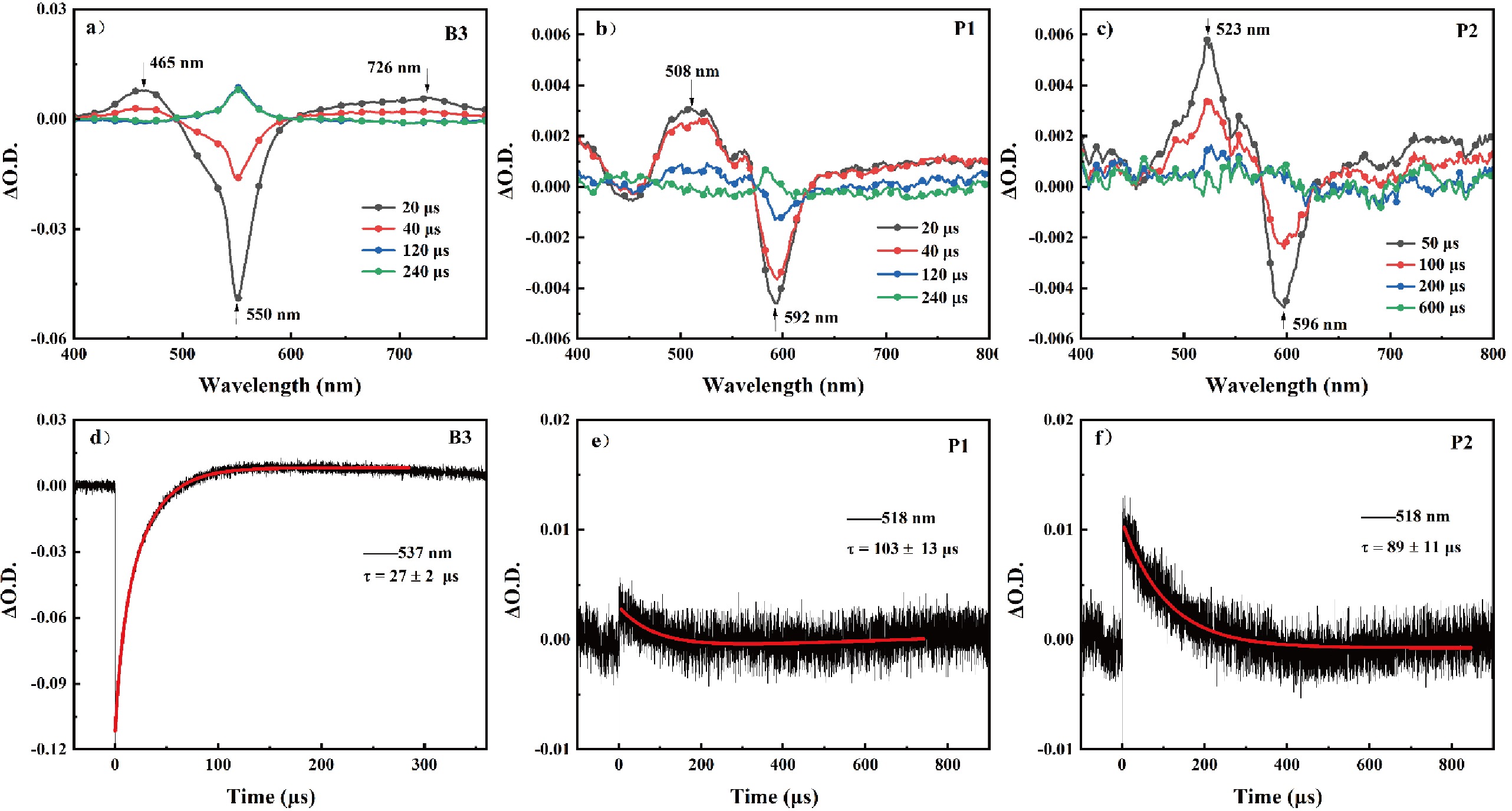

To further explore the photophysical processes of P1 and P2, their triplet excited states were studied by nanosecond transient absorption spectroscopy. When excited at 532 nm, the reference compound B3 shows a strong ground-state bleaching band at 550 nm, consistent with the absorption peak in FIG. 3(a). Besides this, two positive absorption peaks at 465 and 726 nm are observed, corresponding to the triplet state absorption peaks of the diiodo-BODIPY, with a lifetime of 27±2 μs [16]. As shown in FIG. 4(b, c), for P1 and P2, no ground state bleaching attributable to the diiodo-BODIPY moiety is observed, despite the fact that it is predominantly the diiodo-BODIPY part excited at 532 nm. This phenomenon can be ascribed to the rapid energy transfer from the diiodo-BODIPY part to PDA, as previously demonstrated. Both compounds exhibit a negative peak around 590 nm. Combined with the UV-Vis absorption spectroscopy analysis, this peak is identified as the ground-state bleaching peak of PDA. Meanwhile, at 508 and 523 nm, triplet state absorption peaks for P1 and P2 are observed. Furthermore, FIG. 4(a) shows a positive absorption band with the delay time of 240 μs, potentially indicating side reactions of the PSs triggered by strong laser irradiation encountered during the experiment. Similar phenomena can also be observed in FIG. 4(b, c).

By performing kinetic fitting at 518 nm for P1 and P2, the triplet excited state lifetimes of P1 and P2 are determined to be 103±13 and 89±11 μs, respectively, as shown in FIG. 4(e, f). From FIG. 4(e, f), it can also be seen that the maximum triplet state signal for P2 is around 0.01, while for P1 it is less than 0.005, indicating that P2 has a higher triplet state efficiency. This is consistent with the results of the fluorescence analysis.

Considering the fluorescence spectroscopy results, the possible process is as follows: upon excitation of the diiodo-BODIPY part, it first generates a singlet excited state; since Förster resonance energy transfer is faster than ISC, the energy of the diiodo-BODIPY singlet excited state will be transferred to PDA, producing a singlet excited state of PDA [16]; subsequently, due to the presence of iodine, the ISC effect of PDA is enhanced, thereby generating a triplet excited state of PDA.

-

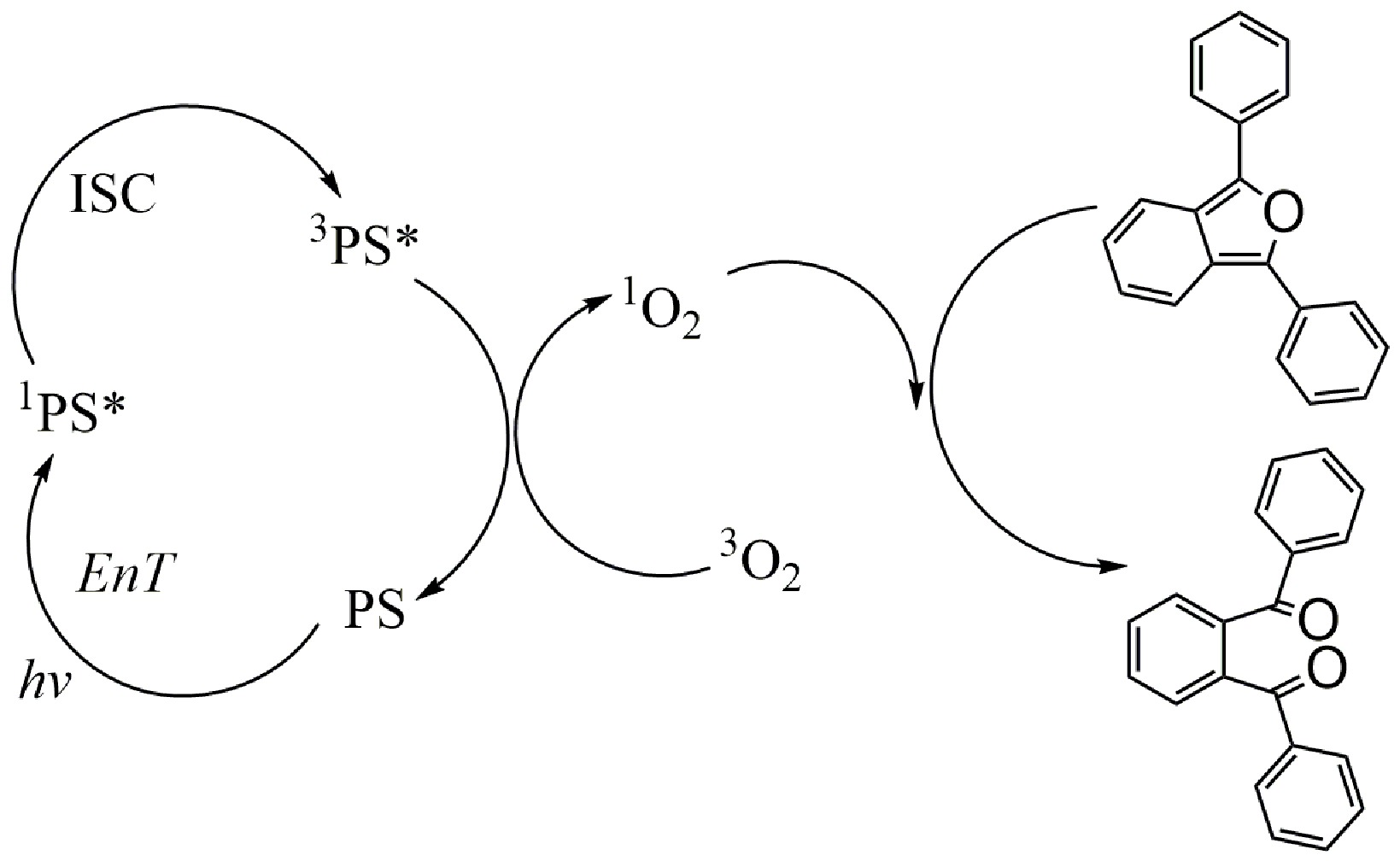

Finally, DPBF (1,3-diphenylisobenzofuran) was employed as a chemical sensor to investigate the photooxidation capacities of P1 and P2. Upon oxidation by singlet oxygen (1O2), DPBF undergoes a ring-opening reaction, transforming its epoxy group into a ketone [25]. This oxidation pathway, facilitated by 1O2, is depicted in Scheme 2. The process begins with the PS being excited from its ground state (S0) to an excited state (Sn). This leads to the formation of a singlet excited state (1PS*), which subsequently transfers to a triplet excited state (3PS*) through ISC. Then 3PS* is capable of sensitizing 3O2 to 1O2, resulting in the oxidation of DPBF to ketones [26]. DPBF exhibits an absorption peak at 414 nm, which notably diminishes upon oxidation by 1O2.

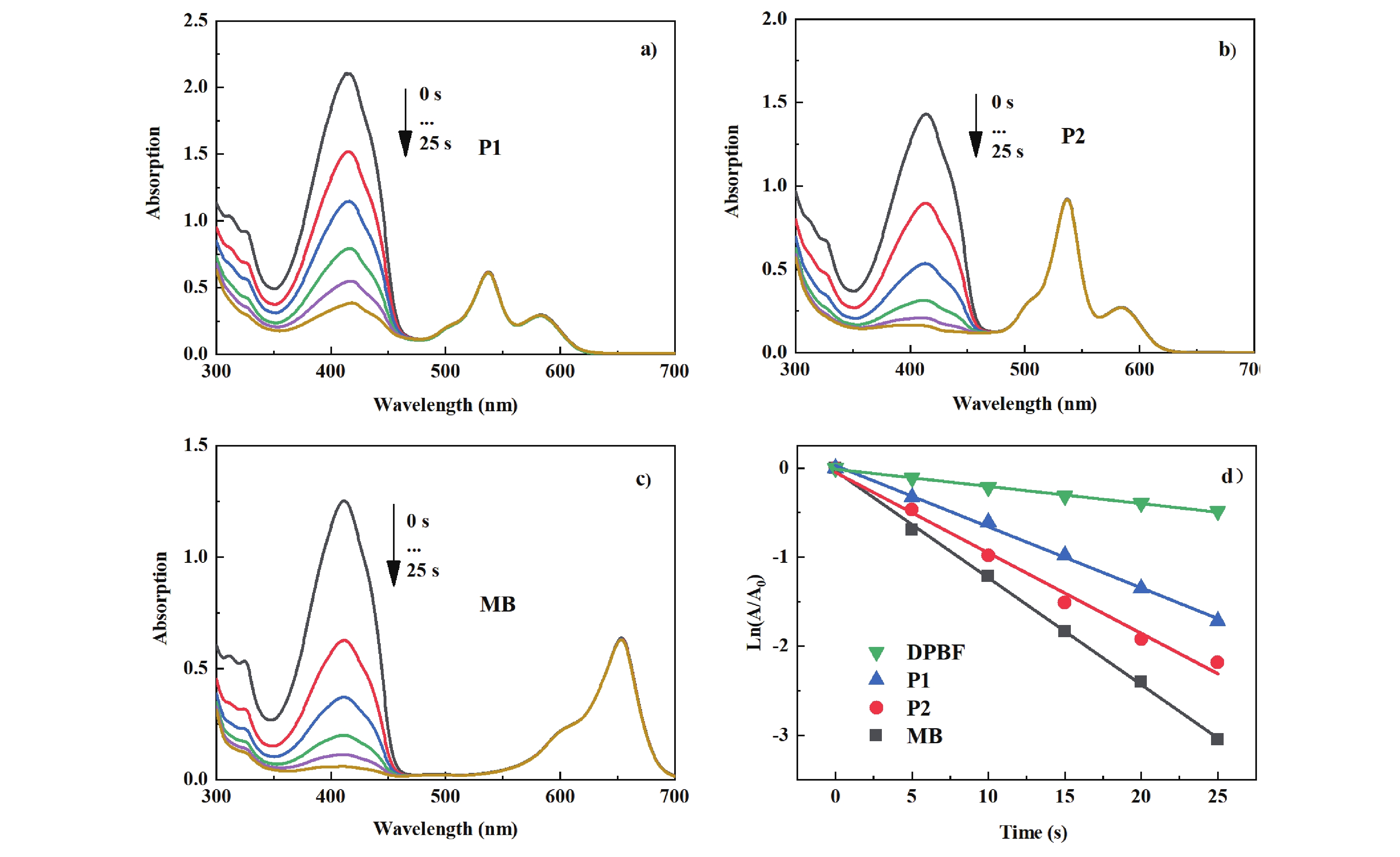

The absorption changes of DPBF in the presence of different photosensitizers including P1, P2 and methylene blue (MB) are illustrated in FIG. 5. The intensity of the absorption peak of DPBF at 414 nm obviously decreases as time extends, indicating that both P1 and P2 possess photooxidative capabilities. The photooxidation capabilities of P1 and P2 were quantitatively compared by plotting the natural logarithm of the ratio of the absorbance at a specific time (A) to the initial absorbance (A0) against the irradiation time. The results are shown in FIG. 5(d) and Table I. It is observable that the photooxidation rate constants of these two compounds are slightly lower than that of MB. The photooxidation rate constant for P2 is 0.904 ×10−3 s−1, which is 1.3 times that of P1.

Using MB as a reference, the singlet oxygen quantum yields (Φ△) of P1 and P2 were also calculated. The Φ△ of P2 is 0.37, while that of P1 is 0.23. The results of the photooxidation are consistent with those obtained from fluorescence and nanosecond transient absorption studies.

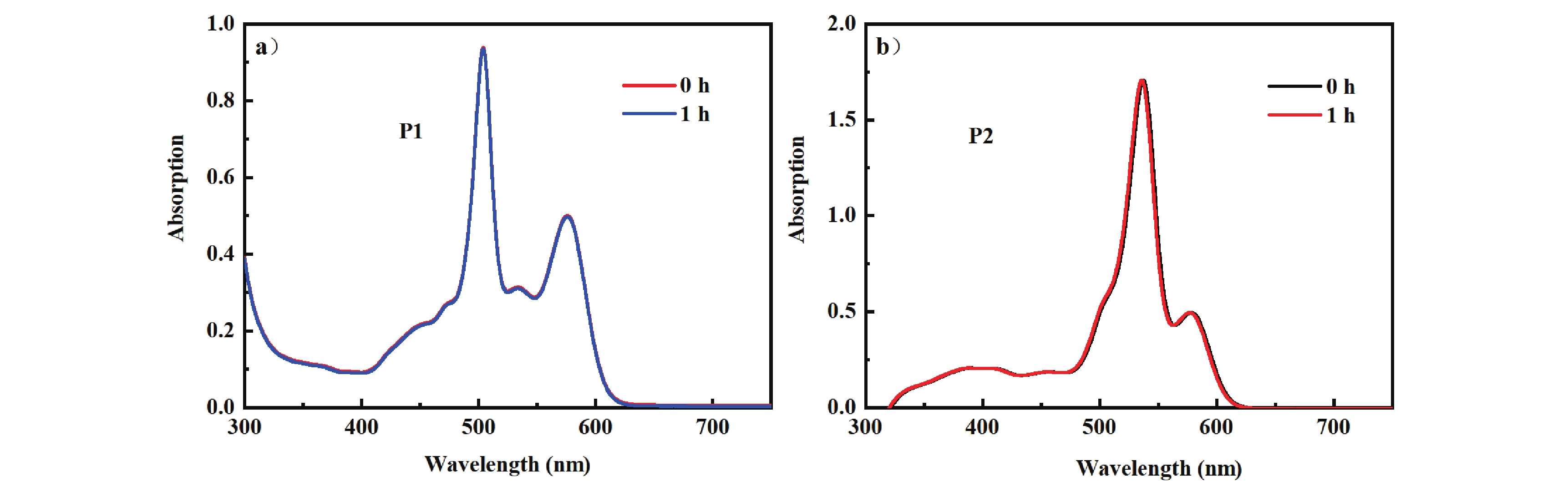

To confirm that the photooxidation capacities of P1 and P2 are not due to their degradation, the photostability of the two compounds was investigated, with the results presented in FIG. 6.

From FIG. 6, it can be observed that after continuous illumination for 1 h, the absorption peaks of P1 and P2 do not change, indicating that P1 and P2 possess excellent photostability. This also demonstrates that the decrease in the absorption peak of DPBF at 414 nm is due to photooxidation, rather than the photodegradation of the PS itself.

-

This study successfully synthesized two new compounds: a dyad P1, containing one diiodo-BODIPY and one PDA unit, and a triad P2, incorporating two diiodo-Bodipy units and one PDA unit. These two compounds exhibit a broad absorption range in the visible light spectrum. Upon excitation of diiodo-BODIPY, it effectively transfers energy from the singlet excited state to PDA. Direct excitation of PDA also results in the observation of fluorescence quenching of the PDA part in both P1 and P2. Following ISC, the triplet excited state of PDA can be efficiently generated. It is worth highlighting that the triplet excited state lifetimes of P1 and P2 are 103±13 and 89±11 μs, respectively, which are significantly longer than that of diiodo-BODIPY. The extended lifetimes of the triplet excited states establish a basis for photobleaching. Both compounds show good photooxidation capabilities, with P2 demonstrating superior performance. Specifically, the photooxidation rate constant and the quantum yield of singlet oxygen for P2 are 1.3 and 1.6 times those of P1, respectively. These results indicate that P2, with two diiodo-BODIPY units, is more efficient in generating triplet excited states, thereby exhibiting superior photooxidative properties. This study provides a crucial foundation for further exploration and optimization in the design of new photosensitizers.

Supplementary materials: The experimental section, molecular structure characterization and spectra are shown.

Broadband Visible Light Harvesting BODIPY-Perylene Dyad and Triad:Synthesis, Photophysical Properties, and Photooxidation Applications

- Received Date: 11/03/2024

- Available Online: 27/08/2024

-

Key words:

- BODIPY /

- Perylene /

- Triplet excited states /

- Nanosecond transient absorption /

- Photooxidation

Abstract: In this study, diiodo boron dipyrromethene (BODIPY) is employed as the energy donor and 3,4,9,10-perylene tetracarboxylic dianhydride (PDA) as the energy acceptor, enabling the synthesis of two new compounds: a BODIPY-perylene dyad named P1, and a triad named P2. To investigate the impact of the energy donor on the photophysical processes of the system, P1 comprises one diiodo-BODIPY unit and one PDA unit, whereas P2 contains two diiodo-BODIPY moieties and one PDA unit. Due to the good spectral complementarity between diiodo-BODIPY and PDA, these two compounds exhibit excellent light-harvesting capabilities in the 400–620 nm range. Steady-state fluorescence spectra demonstrate that when preferentially exciting the diiodo-BODIPY moiety, it can effectively transfer energy to PDA; when selectively exciting the PDA moiety, quenching of PDA fluorescence is observed in both P1 and P2. Nanosecond transient absorption results show that both compounds can efficiently generate triplet excited states, which are located on the PDA part. The lifetimes of the triplet states for these two compounds are 103 and 89 µs, respectively, significantly longer than that of diiodo-BODIPY. The results from the photooxidation experiments reveal that both P1 and P2 demonstrate good photostability and photooxidation capabilities, with P2 showing superior photooxidative efficiency. The photooxidation rate constant for P2 is 1.3 times that of P1, and its singlet oxygen quantum yield is 1.6 times that of P1. The results obtained here offer valuable insights for designing new photosensitizers.

首页

首页 登录

登录 注册

注册

DownLoad:

DownLoad: